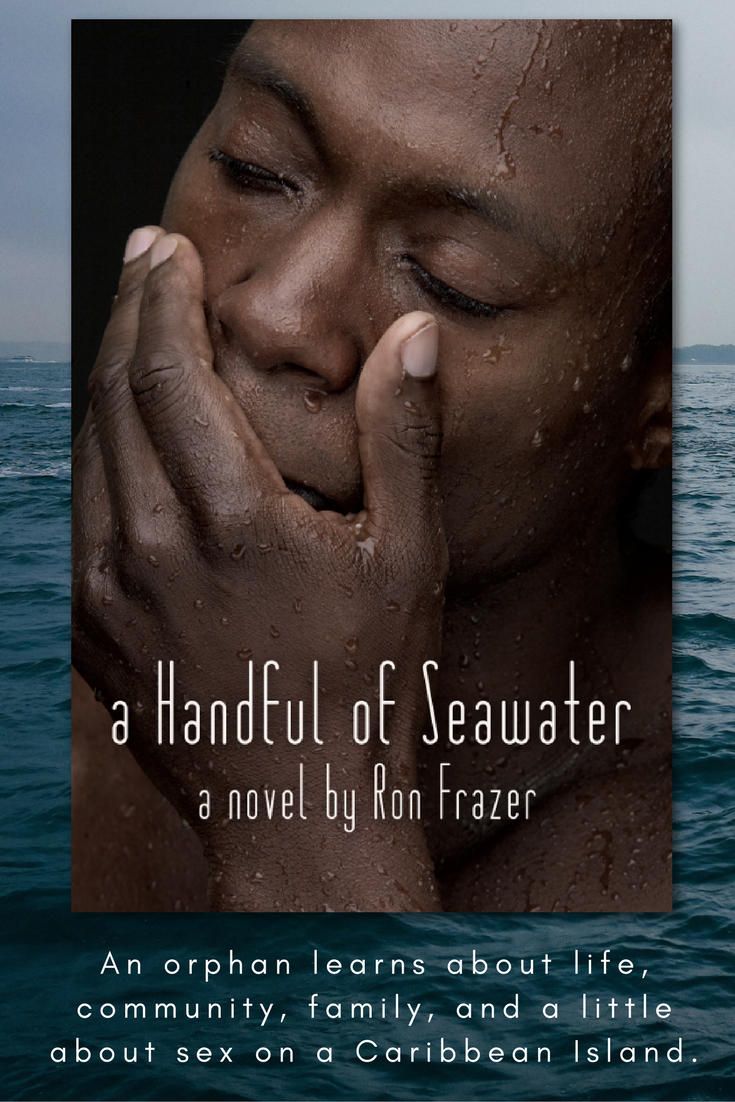

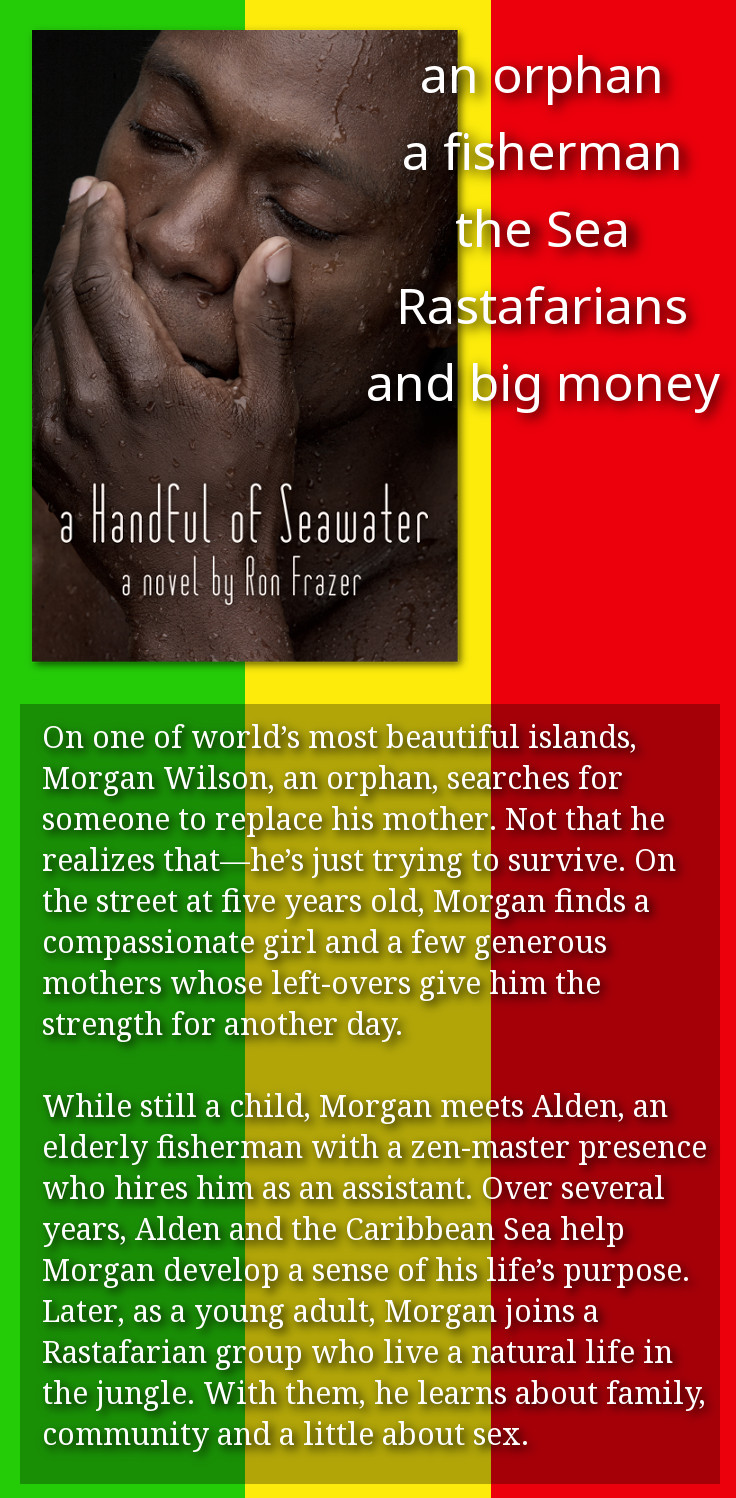

Synopsis of A Handful of Seawater

The Sea, the Jungle, and Zen

“As the child went to sleep, his mind drifted to thoughts of his mother—of being pressed against the great wall of her back as she slept next to him. He wanted someone to care that he ate and washed. He wanted to be touched the way his mother’s hand would stroke his hair or press his shoulder when she sent him to play. The other boys may not have fathers, but they all had mothers. He felt cheated and alone.”

On one of world’s most beautiful islands, Morgan Wilson, an orphan, searches for someone to replace his mother. Not that he realizes that—he’s just trying to survive. On the street at five years old, Morgan finds a compassionate girl and a few generous mothers whose left-overs give him the strength for another day.

While still a child, Morgan meets Alden, an elderly fisherman with a zen-master presence who hires him as an assistant. Over several years, Alden and the Caribbean Sea help Morgan develop a sense of his life’s purpose. Later, as a young adult, Morgan joins a Rastafarian group who to live a natural life in the jungle. With them, he learns about family, community and a little about sex.

Morgan’s life can be a metaphor for the lives of all of us. We are all alone in one sense, and often searching for something that we can’t quite name. If you have ever wondered about the meaning of life, you might discover glimpses of it while accompanying Morgan in this Caribbean adventure.

Chapter 1: The Counterfeit Sock

Sitting on a creaking stool, Morgan used a rusted machete to slice ten inches from the sleeve of a faded, black jersey. He peered into the predawn gloom of the other room to see if his uncle Sean stirred from the noise, but the old man, smelling of rum, sweat and urine, was sprawled on his bed in yesterday’s clothes, still drunk from the night before.

Only the orange glow of a candle relieved the blackness of the unpainted shack. The single layer of grimy boards that formed both the outer and inner walls of the two small rooms reflected almost no light, and the underside of the tin roof, blackened with forty years’ accumulation of soot from kerosene lamps and candles, reflected even less.

It was Monday. Morgan took his only secondary school uniform from a plastic grocery bag that hung from a nail in the wall. He put on the rumpled but clean, white shirt, and the gray, hand-me-down slacks that ended an inch above his ankle. The pants were tight; he had trouble with the button and the fly. He’d also outgrown his belt over the summer.

He put on his left sock and shoe then arranged the amputated sleeve on his right foot so the elastic cuff ringed his ankle. Holding the jagged end between his toes, he slipped on the right shoe. The sleeve tried to disappear into the shoe; he pulled it up so it covered his ankle.

He stood and looked down. Even by candlelight, the pants revealed the deceit. The elastic wasn’t tight around his ankle; it had fallen into a pile against the top of the scuffed leather. He tugged at his pants to lower them a little but couldn’t make them reach the top of the drooping sock.

He knew his mother would never have let him go to school looking like this. She would have found some way to get him a uniform that fit.

He couldn’t remember her well; she had died ten years ago when Morgan was five. There was a hazy memory of her smiling as she smoothed his clothes before they walked out the door to go to church. His mother’s face faded into that of the government social worker who had forced him to live with his worthless uncle.

Morgan combed his hair looking in the hand mirror rimmed in pink plastic that hung on a nail in the wall between the two rooms. He hated his face; it was too black. He grimaced, mocking his two missing front teeth. His fingers traced several keloid scars on his cheeks and forehead while he glared into his own eyes until the skin disappeared and only the eyes remained.

He poked a chunk of bread into one cheek, put a little saltfish in his mouth and blew out the candle. He stepped through the decaying door onto the rock that served as a front step, and carefully closed the latch without a sound. He exhaled deeply to rid himself of the stink of his uncle and the mildew of the shack. Then he took several deep breaths to fill his lungs with the moist, musty trade winds that were blowing the morning mists from the jungle-covered mountains that ran like a spine from Sauteurs, at the north end of the island, to Morne Jaloux at the south end. Making sure he walked only on the silent, stable rocks, he stopped at the back of the shack where he was hidden from the street. He reached under the shack to retrieve the soup can that kept his money safe from the old man, took a dollar for his lunch and slid the can back into its hiding place.

Standing there on a hill that rose 200 feet above the town of Victoria, Morgan looked west across the town toward the sea as the sun broke over the mountain behind him. The turquoise of the Caribbean glittered as the sun danced on the white sand below the clear, shallow water that sloshed silently at the shore as if the vast sea were a small lake. As the sun rose further above the mountain, it flooded the beach with pink light that blazed on the galvanized steel roof of the little house where he once lived with his parents. He stared at it a moment wanting some feeling to come but it refused. He returned to chewing his bread and saltfish as he began his walk to school.

About 100 feet along the broken asphalt road that wound down the hill to the town, he stopped to rinse his mouth at a standpipe. A rotund woman in a tight, translucent slip was washing a naked baby. He watched her huge breasts wobbling from side to side as she rinsed the baby and filled a plastic pitcher for her family’s breakfast. After she moved away, he rinsed his mouth leisurely while watching her back—how the fat from her breasts ran under her arms and reached almost to her spine. He spit into the trash lining the ditch, then drank several handfuls of water to last him until he reached the school.

The road was coming alive. Women were washing, cooking or heading out to the fields with baskets on their heads and machetes in hand. Younger women who were no longer in school were braiding each other’s hair and laughing. Men sat on boulders along the road, some alone, some talking in small groups, smoking and waiting for their women to clear out so they could head for the rum shop without censure.

Morgan continued down the cratered road into the town, always looking down to make sure of his footing. Once there, he walked five blocks through the narrow streets that contained the concrete houses of the village elite—the taxi drivers, shop owners, and government workers.

As he reached the main road, he turned north toward his school. It was cool in the shade of the cliffs to his right as he left the voices of the village behind him. Small waves slapped against the rocks to his left. He stood for a moment and listened to the drone of small outboard motors. Looking south he saw three skiffs heading out to sea.

After walking a few more minutes Victoria was out of sight. He leaned against the cliff and looked out to sea across the remains of the road. He felt a part of that sea, a part of the wind; he felt at home. With a sigh, he renewed his walk, scuffing his feet in the dirt of the road which had been destroyed by a storm the previous year; the broken sections of asphalt washed out to sea or scattered among the rocks on the shore.

After a mile or so, an old flatbed Bedford truck came from behind and rattled past him, swirling a cloud of dust. It carried the children from the village who could afford fifty cents for the ride. The red, yellow and green truck had no seats, just six two-by-twelve boards forming crude benches shaded by a canvas canopy. Morgan watched the bottoms of the school-girls bouncing on the planks as the wheels hit pothole after pothole.

A half-hour later, when Morgan reached the Waltham Secondary School, the children were lined up in their separate classes on the grassy slope between two long concrete shelters that served as classrooms. Each of the three classrooms in each building had walls of rusted wire mesh on the east and west sides to let the trade winds pass through. The north and south walls were concrete with chalkboards made of warped pressboard painted black.

The principal, Mrs. Phillips, was making announcements while the teachers took attendance. As Morgan slunk along the building, trying to be inconspicuous behind the group, children turned and snickered.

He found his place in line. All the children in his class smiled in his direction as if helping to draw the teacher’s attention to his tardiness. Before that could happen, Thomas, the class clown standing right behind him, noticed his right foot.

“What man! You think dat a proper sock!”

He pointed and a brief wave of snickering drifted through the class.

Another boy bent down to get a better look, “Naa man! Dat a sleeve, you know! Look man! Morgan make a new sock!”

The snickering grew louder then faded into whispers. Morgan hung his head, but not in shame. He was a junk yard dog of a boy; his anger brought his shoulders up and his head down. He glared at his persecutors through his eyebrows as he imagined the punches that he would land if he could. The scars on his face, his unblinking eyes, and the thin line of white where his snarl exposed his teeth would have silenced them if the principal hadn’t moved in their direction and ended the whispers. She stood in front of Morgan and stared at the class with her “not another word from any of you” expression.

Mrs. Philips was a large, kind and sympathetic woman who knew Morgan’s story. She watched Morgan’s face change from rage to embarrassment. The children were pointing at his feet. Mrs. Philips stepped back a few steps to study Morgan’s feet, her head tilted to the left. The walk to the school had so stretched the elastic that the “sock” now looked very much like a sleeve. She wagged her finger at the class with a look on her face that would silence the rowdiest of them.

“I think Morgan is a very resourceful fellow, you know! You children could all take a lesson from him. What would you do if you found yourself with only one sock?” She sucked her teeth as if to say that she didn’t have much hope for them, “I think Morgan is very creative.”

She had shamed them for the moment, but the students began laughing once they were dismissed to go to their first class. Morgan wanted to go back home and change into his shorts and T-shirt so he could go fishing with Alden, but he knew that by then the old man would have been well out to sea. He went to his first class and pretended to listen.

Throughout the long, angry morning, he overheard Thomas and the others making sporadic jokes about him. At lunch time he walked down to a shop and bought a piece of bread and a grape drink. It felt good to get away from the other students.

As he chewed the bread he thought about how much he hated going to school. He appreciated the kindness of Mrs. Phillips but it wasn’t enough to soothe the pain of ridicule by boys with mothers. Throughout the morning he despised the nicely pressed pants that Thomas wore and thought the polished black shoes made Thomas look like a girl in church.

Morgan was jealous of all the boys. Some of them were dressed better than others but they all looked better than him.

By the afternoon, the students had grown tired of joking about the sock so they left Morgan alone. But Morgan hadn’t let it go; he continued to think of ways to get back at them—ways that he’d never put into action.

The closing bell rang. The Victoria students walked out to stand by the main road and wait for the Bedford truck to pass by on its way south from Sauteurs to Victoria. The students from the northern villages formed another little group waiting for a bus going the opposite way.

Morgan slipped along the edge of the crowd and out onto the road heading south toward Victoria. He could hear Thomas shouting some joke about him for the benefit of the others, but he couldn’t really hear the words. As he neared the first rum shop, the voices and laughter of the students were replaced by the rush of the sea breaking against the rocks to his right.

Further down the road he walked past five houses, evenly spaced along the road about fifty feet apart; there were two wooden shacks and three small concrete bungalows, all unpainted but neat. They were located on a slight slope about thirty feet from the road where the land rose up into the jungle. The earth around each house was swept clean. The bare feet of the ever-present mothers and children had packed it hard and smooth. As in villages throughout the island, the people lived outside; the houses were just for sleeping and storing their few possessions. Only a few old people and the rich lived in their houses during the day.

Morgan watched the small children running and laughing around the houses, and the mothers watching over them. One woman was pressing a friend’s hair using a metal comb, heated on a small coal fire beside her to keep the heavy comb at the right temperature. As each woman spoke the other would laugh. The woman holding the comb laughed like his mother, a loud open-mouthed HAH!—just a single sound, sharp like a dog’s bark.

As he walked further into the silence of the road, he thought again of his classmates and their mothers fussing over their meals and appearance as they left for school. Then his mind drifted to thoughts of his mother holding him at night as they went to sleep and the great wall of her back as she slept next to him. He wanted someone to care that he ate and washed. He wanted to be touched, the way his mother’s hand would touch his hair or shoulder when she sent him to play. The other boys may not have fathers, but they all had mothers. He felt cheated and alone.

Yeh Man! I hated dem boys when I small. Dey so cocky, you know. Dey so smart in dem pressed pants and ting. Dey look down on I. Dey cowards, you know. Dey even scared of de sea! And dey livin’ right by it! But de sea, it like me mother, you know, and Alden me father. De sea a different world, a better world, man.

He looked around him. He was walking along the sea in the one stretch where there was nothing man-made except the road. The angry and lonesome thoughts drifted into a sense of freedom—of being by the sea, listening to its soothing voice. He crossed the road to sit on a large rounded rock that lay half-buried in the sand between the pavement and a narrow beach. Gulls were crying and circling overhead. He watched small crabs scurrying over the rocks in a tide pool. There were minnows in the clear water nibbling on bits of food.

He felt a part of their world, but that feeling was stronger when he was on the sea with his old friend Alden, bringing up nets full of big fish together with little crabs and minnows that would have to be sorted out and thrown back. He was part of two worlds—a part of that hateful school where he was ridiculed and controlled and a part of the sea with its quiet, its solitude, and its freedom.

The roaring Bedford startled him as it passed heading south. For a few seconds through the dense dust that almost erased the truck from his view, he could hear the others laughing. He assumed that this time they weren’t laughing at him, but for a moment he hated them anyway. Then the voices of the sea drowned them out. The bus disappeared around a curve, and he sat watching a crab nibbling on a bit of fish.